|

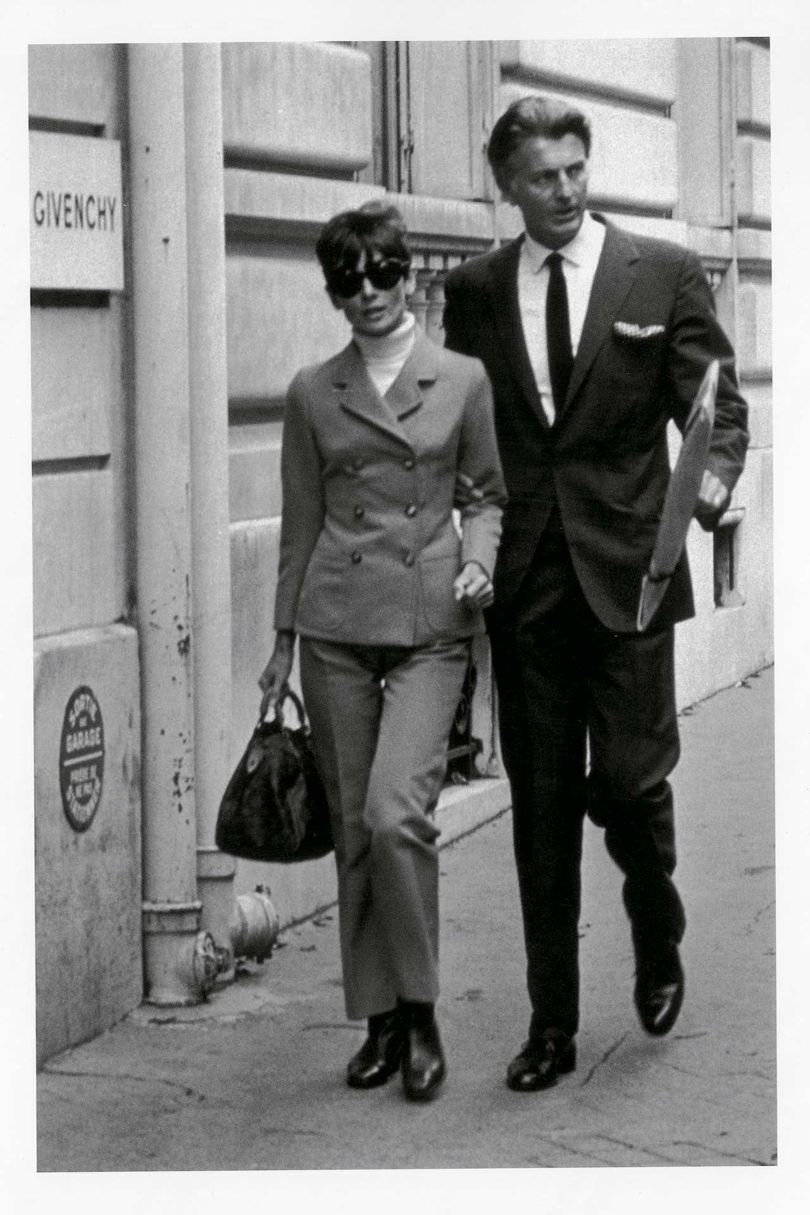

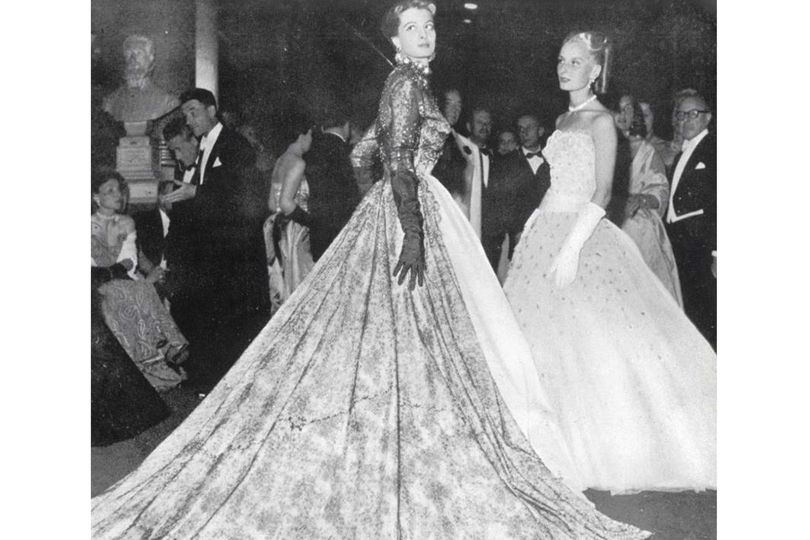

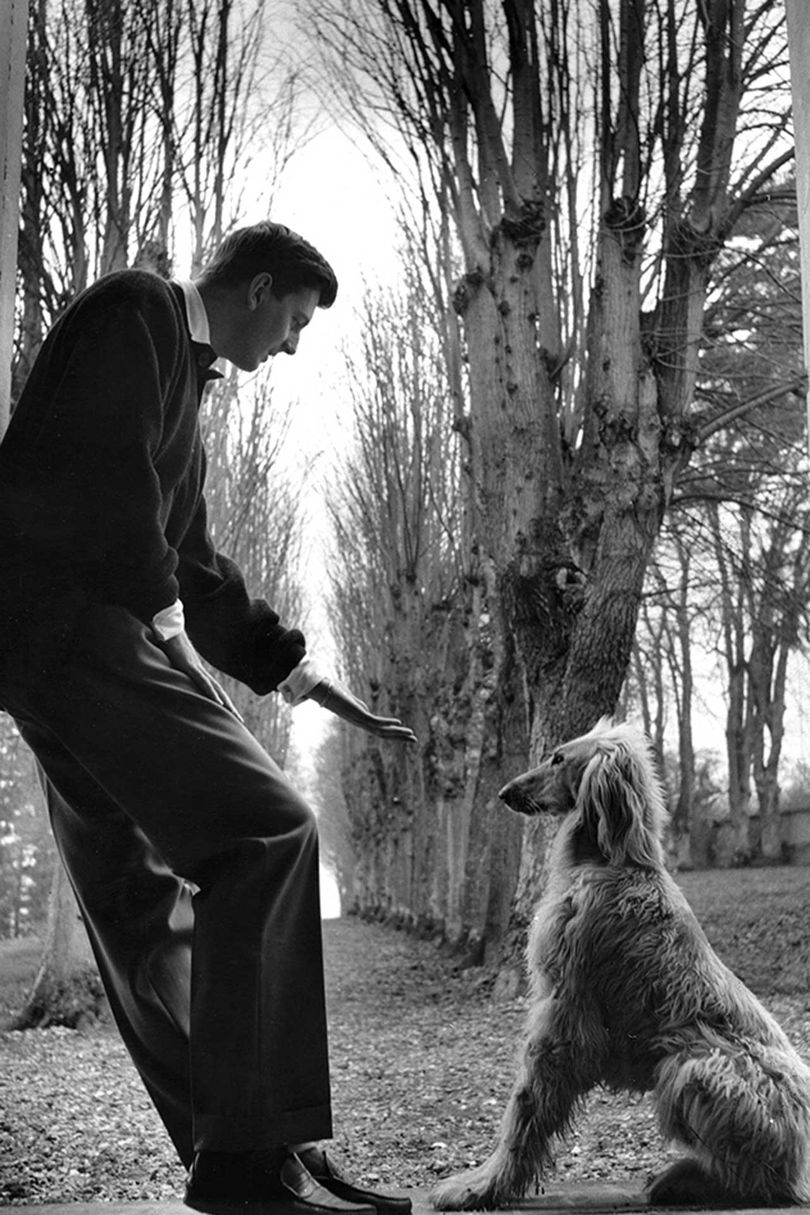

敬请期待中文版 when I visited a windswept Calais last June, I knew it would be an exceptional opportunity to talk to Hubert de Givenchy. The great couturier was showing his work in the Cité internationale de la Dentelle et de la Mode de Calais (the Museum of Lace and Fashion), on France’s northern coastline. I was overwhelmed to learn, in the designer’s own words, the legacy of the clients and Parisian haute couture world that made him unique. Here is his story. May he rest in peace. Hubert de Givenchy, tall, noble and impeccably tailored, is telling me a story about dressing the Duchess of Windsor, whose husband gave up the throne of England for the woman he loved. “The Duke didn’t speak French – he spoke Spanish, German and, of course, English,” the couturier remembers. “He said to me, ‘Givenchy, you know, I really like what you do for the Duchess.’ But just as I replied, ‘Thank you, it’s very kind of you to tell me that, it’s very encouraging,’ he suddenly asked me, ‘Why is the price so high?’” Enter the Duchess, with a new bouffant hair-do by Alexandre, trying to smooth things over: “Do you think the price is so high for all the joy and pleasure I give you with all the lovely dresses Hubert has designed for me?” Givenchy has a wicked twinkle in his eye as he relates more tales of the ladies he loved to dress. The couturier is now 90 and gave up his couture house in 1989, after it had been bought by LVMH. But he still has a precise memory of the key moments in his long career and brings all to vivid life in the clothes displayed in the Museum of Lace and Fashion in Calais, on France’s northern coast.  An Hubert de Givenchy gown worn by Audrey Hepburn in Sabrina (1954). The film won an Oscar for its costumes Getty While visiting gallery displays, I have often thought “If only these clothes could speak.” But I needed no magic spell to discover why Audrey Hepburn chose a lacy, racy, little black dress for the Sixties movie, How to Steal a Million; or to learn what French President General de Gaulle said to First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy as she glided into the Palace of Versailles in her swishing Givenchy dress, with its embroidered silk and pearl flowers.  A Givenchy cocktail ensemble, comprising dress and jacket in Chantilly lace, worn by Audrey Hepburn in William Wyler's How to Steal a Million, 1968 Givenchy. Photo by Luc Castel “Jackie was very modern; her spirit was modern, she was a new image for America because he was a young president,” Givenchy says as he conjures the young couple to life, as they were at the dawn of the 1960s.  Detail of a Givenchy satin evening ensemble, comprising a dress with an embroidered bodice and a coat, worn by Jackie Kennedy for an official visit to France in Summer 1961 Givenchy. Photo by Luc Castel “It was not the same relationship or friendship that I had with Audrey,” the couturier continues. “The American people felt emotion for Jackie, but they preferred to have an American couturier design her dresses when they came to France for a state visit. Jackie asked for more than 10 or 15 pieces, saying ‘I don’t know if I can be dressed by a French designer.’ We did all the fittings in secret. Then after the event at Versailles, Jackie sent me a little postcard to tell me that General de Gaulle gave her a very nice compliment. He said, ‘Madame, this evening you look like a Parisienne.’”  Hubert de Givenchy and Audrey Hepburn in Paris, 1960s From the collection of Hubert de Givenchy Having the designer tell me, in his own words, the story behind the 80 outfits on show, brings to life what might have been a pleasant but predictable exhibition. Similar shows have already been held in the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum in Madrid, in The Hague and in Switzerland. The funeral outfit made for the Duchess of Windsor by Hubert de Givenchy whose hand workers produced it in just TWO days for the service in I gazed at two visions of the Duchess of Windsor: laughing over the black-and-white striped dress that both she and the Baroness de Redé were wearing at the same Paris event, and dressed for her husband’s funeral in a tiny coat, dress, and pillbox hat. The all-black outfit, produced by Givenchy through two days and nights of work, was finished just in time for the plane arriving to take the Duchess to an icy reception in England.  The Duchess of Windsor wore a Givenchy suit for the funeral of her husband, Edward VIII. Givenchy had only two days to make the couture ensemble Getty She greeted the designer with the words, “Hubert, it is really marvellous.” “But I said, ‘No, it is normal; it is my job to do that,” Givenchy recalls. “Although there is a lot of criticism about the Duchess, she was very amusing and entertaining.” The concept of clothing as a direct relationship between couturier and client is now a distant memory, but brand Givenchy has continued to function, first with John Galliano as designer (before he went to Dior), then Alexander McQueen, Julien Macdonald, and more recently given an international hip and cool style by Riccardo Tisci, who has now passed the baton to incoming designer Clare Waight Keller. Against the current background, it is hard to understand that almost every garment in the exhibition has a personal story, whether it is the white cotton froth of a blouse beloved by model Bettina in the 1950s, at the start of Givenchy’s career, or the black sheath dress, set off with pearls, worn by Audrey in Breakfast at Tiffany’s in 1961.  The Givenchy evening sheath dress worn by Holly Golightly, as played by Audrey Hepburn, in the opening scene of the Blake Edwards film, Breakfast at Tiffany's, 1961. Following its debut in the film, the black sheath has become an eternal element of the style lexicon Givenchy. Photo by Luc Castel  Seen from the back, the evening sheath dress worn by Holly Golightly, as played by Audrey Hepburn, in the Blake Edwards film, Breakfast at Tiffany's, 1961 Givenchy. Photo by Luc Castel The list of private loans – from the Countess de Borchgrave to the Duchess of Cadaval and the Marquise of Llanzol – suggests a society so profoundly different to that of today that it appears to belong to a different universe. And Givenchy, who retired in 1995, knows that not only does he personally no longer have clients, but that his fashion world no longer exists. Yet he says, rather touchingly, that he continues to draw, as he has always done, but especially in memory of Audrey. A video tucked into a narrow alcove of the museum shows the designer and his coloured pencils at work One dress that ticks all the boxes in this museum devoted to the creation and treatment of lace (and housed in an original lace factory) is a voluminous yet fluid ballgown from 1952 for the Versailles ball, made for the French model and later actress, Capucine. When I complement him on this, Givenchy’s comment is that Balenciaga was the couturier who knew better than any other how to use lace.  The French actress Capucine (the future star of The Pink Panther and What's New, Pussycat?), wearing Givenchy at the Versailles ball in 1952 Givenchy The overall impression of Givenchy as a designer is that he liked to have a powerful role model to subsume into his own work. His great fashion hero was Cristóbal Balenciaga, but the 1980s Givenchy outfits – such as the scarlet dress printed with the motif of an ostrich feather fan as held in the model’s hand – suggest a penchant for Yves Saint Laurent. But Le Grand Hubert, as the French describe him, has an elegant enchantment – not least in a display of hats, feathered and flouncing – that are a memory of fashion’s once consummate elegance.  Givenchy with his Afghan hound in 1955. At 6'6", Givenchy was given the nickname, Le Grand Hubert Getty (责任编辑:admin) |